Beneath the Hood: Testing Aflatoxin in the 1980s

//memory fragment.awen.null I was twenty-two and felt indestructible. That’s the only explanation I have for why I volunteered so readily to work on Aflatoxin testing in the Ministry of Agriculture’s food safety lab back in 1983.

//memory fragment.awen.null

I was twenty-two and felt indestructible. That’s the only explanation I have for why I volunteered so readily to work on Aflatoxin testing in the Ministry of Agriculture’s food safety lab back in 1983. Looking back now, with the benefit of age and decades of research hindsight, I can say this with no irony: we were working with one of the most potent natural carcinogens known to science—half-blind and half-mad in a haze of chloroform and optimism.

At the time, aflatoxins were emerging as a serious concern in imported food products—particularly in peanuts, maize, and dried figs. Produced by strains of Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus, these mycotoxins had been implicated in liver cancer outbreaks in both humans and livestock. The Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF) had begun tightening its protocols, publishing guidance and internal papers that warned of the dangers—but implementing those safety precautions in practice was another matter entirely.

We weren’t cowboys. We wore gloves, lab coats, and operated under fume hoods. But our understanding of chronic exposure risks was limited, and much of the equipment would be considered primitive today. We worked with open-topped beakers, glass columns packed with silica gel, and heavy glassware that could break with a slip of the wrist. And then there were the solvents: chloroform, methanol, acetone—all in generous supply and all handled with the sort of casual confidence you’d expect from a group of young microbiologists who still went out drinking after work, reeking of aldehydes.

The Process

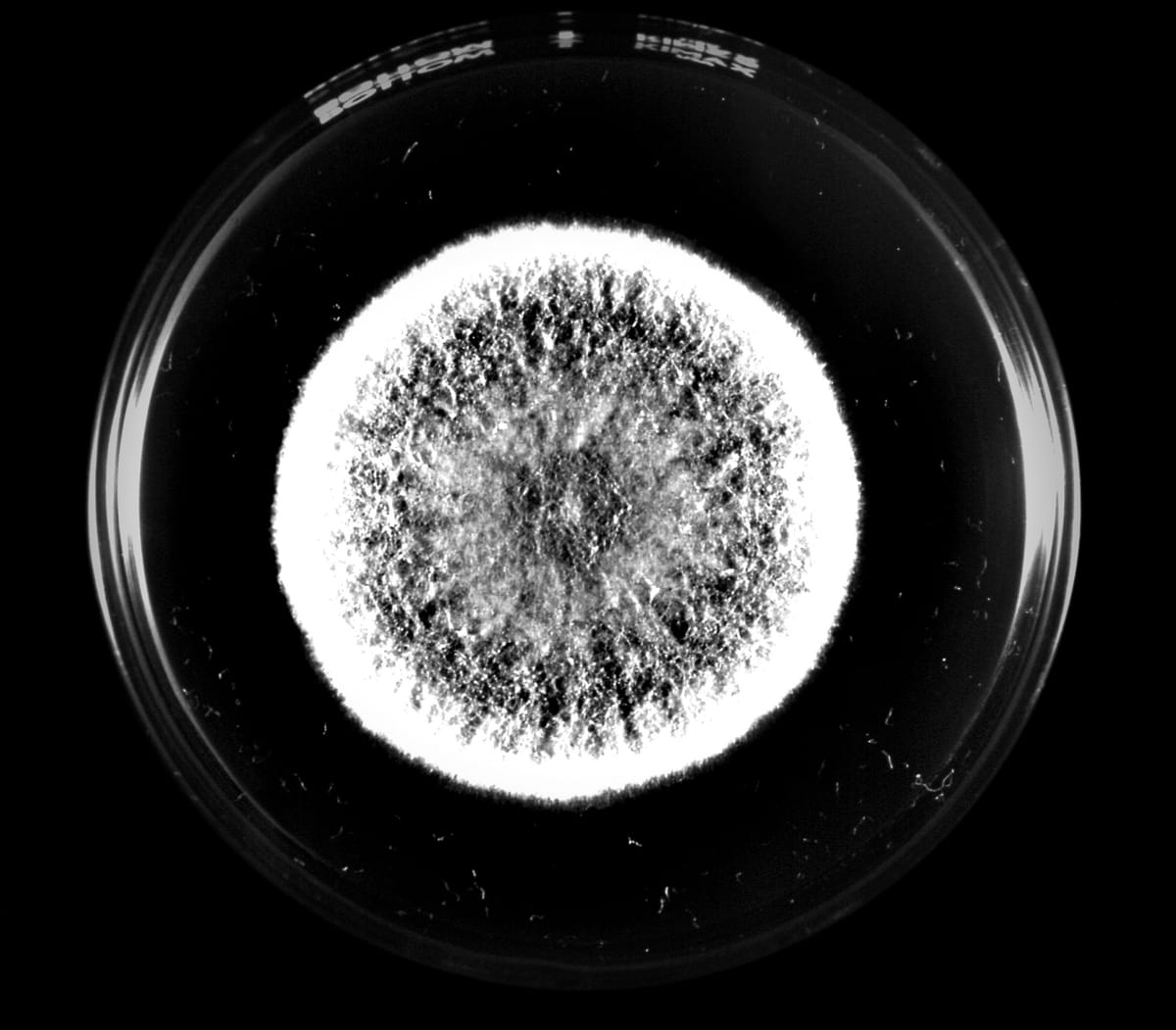

The testing process began, predictably, with Aspergillus cultures. We’d receive contaminated samples or intentionally inoculate sterile substrates—usually crushed maize or rice—with A. flavus spores. Incubated at around 28–30°C, the cultures bloomed into vivid green colonies with that unmistakable dusty texture. To this day, the smell of Aspergillus—earthy, almost sweet—is burned into my memory. Like damp straw laced with death.

After about a week, the aflatoxins would be extracted using a solvent like methanol-water (often 80:20), then partitioned into chloroform. Chloroform was the magic key—it separated the aflatoxins from the bulk of the aqueous residue. But chloroform, as we later came to understand more fully, was itself a carcinogen, and one that penetrated latex gloves with ease.

We’d shake the separating funnels by hand—sometimes with a thumb over the glass stopper, rather than a proper cap—venting periodically to release pressure. Occasionally, someone would forget and a plume of solvent-saturated air would escape into the lab like a warning sigh. You’d get used to the dizzy spells, the slight metallic taste in the mouth. We joked about it. In hindsight, the joke was probably on us.

Once the extract was ready, we’d concentrate it using a rotary evaporator—often without a water bath—then run it through thin-layer chromatography (TLC). You’d spot tiny aliquots of the extract onto silica plates alongside standards—Aflatoxin B1, B2, G1, and G2—all glowing faintly under UV light. The TLC chamber was usually lined with a benzene-based mobile phase, the fumes of which clung to your skin for hours.

We handled aflatoxin standards with shaky reverence (Aflatoxin B1 remains one of the most potent, naturally occurring carcinogens ever identified). Microgram-per-millilitre solutions stored in crimp-sealed vials, they could cause irreversible damage in the tiniest amounts. And yet we handled them with open pipettes—something I’m deeply ashamed to admit now, but it was the culture of the time. You didn’t question the old hands, and there was an unspoken pressure to prove yourself capable of handling “the hot stuff.”

A Natural Killer

Aflatoxins, especially Aflatoxin B1, are mutagenic, hepatotoxic, and immunosuppressive. Back then, the foundational papers by Wogan, Van Egmond, and others had already established links to hepatocellular carcinoma. The 1980s literature was full of animal studies—rats and trout fed contaminated feed and developing tumours at alarming rates. We read them with clinical detachment, never quite connecting the dots back to the TLC plates glowing blue under our noses.

MAFF guidance was evolving during this time. I recall internal memos from 1984 cautioning against overexposure and recommending use of charcoal filters, glove changes, and stricter waste protocols. But these warnings took time to filter down. Many of us had grown up in labs where agar was poured by hand, not autoclaved in sealed vessels. We were slow to modernise.

Youth and Illusion

I look back now and realise how little I understood of the danger I was in. I was focused on the method—getting clear separation bands, extracting at the correct pH, recovering microgram quantities without loss. There was a thrill to it. Precision work, in a fog of volatile death.

We were trying to protect the food chain, of course. That was always the justification. Testing for aflatoxin levels in imported grains and nuts helped prevent outbreaks like the one in Kenya in the 1970s, where over a hundred people died from consuming contaminated maize. But it wasn’t until much later, when I moved into pharmacology, that I fully grasped the cumulative risk we’d exposed ourselves to.

Aflatoxins remain a threat today—climate change and poor storage conditions are only making fungal contamination more common. But the analytical techniques have improved dramatically: HPLC, ELISA kits, digital fluorometers. Modern labs are clean, automated, and properly ventilated. But part of me remembers the old ways, the danger in every step, and the invisible toll it may yet take.

Closing Thoughts

If you were to ask me now whether I regret it, I’d pause. Working with aflatoxins taught me respect for the unseen. The way a single fungal spore can bloom into a toxic bloom of molecular violence. The way scientific inquiry—however noble—can exact a cost from the bodies of those who carry it out.

This wasn't a job for the faint-hearted. But it was part of a world that made me who I am. And for better or worse, the ghost of Aspergillus still haunts my memory, fluorescent and silent under a UV lamp.